Christine Shergold is the Manager, Special Projects at State Records NSW. This is her Staff Pick.

I don’t have any favourite archives per se. There are many that make me smile or laugh, or conversely sadden or distress me. Others impress me with their beauty or their utility. Most of the archives however don’t affect my emotions, apart from that general feeling of frustration experienced by many in trawling through the records.

Finding archives about archives

In carrying out their day-to-day functions and operations New South Wales Government agencies leave trails of information about themselves and their records. Absolute pleasure comes from the discovery of those elusive facts and pieces of information that I know can be found among our records. Much of this information is in voluminous correspondence series which complicate their finding. One has to be like Sherlock Holmes, using a virtual magnifying glass to find clues and pointers to sources of desired information.

My favourite archives are those which elucidate – what records were created, how they functioned, how they changed over time, if they were transferred to another agency; what happened when in an agency, when was a branch or division created and/or abolished, how the functions of an agency or branch changed over time (contracting or expanding); and so on. Particularly appealing are lists of records at a given point in time which frequently tell us about records which have not survived.

The mystery of ‘missing’ Convict records

State Records is fortunate in having the oldest collection of official records in Australia (as the first European colony on the continent) including an extensive collection documenting the ‘careers’ of over 80,000 convicts transported between 1788 and 1842. These world heritage listed Imperial Convict records however do have many gaps; it is quite clear that many records relating to the system put in place to manage the Convicts and their movements have not survived.

Some time ago I was pleased to have the opportunity of tackling the question of what did happen to those Imperial convict records that are no longer extant – settling once and for all, if possible, the persistent myth that large quantities were dumped into Sydney Harbour or ‘at sea’. (Or were they destroyed in the Garden Palace fire instead?)

Discovering a 19th Century records disposal schedule

Rising to the challenge, after taking a number of wrong turns and suppressing rising levels of frustration, I managed to find enough information in the archives to show that the sea was not involved in any way with the destruction of Imperial Convict records. One of the fabulous and informative sources that I managed to locate is a 1880 Colonial Secretary in-letter (Colonial Secretary: Main series of letters received, NRS 905, CSIL 80/6527 in [1/2492]). CSIL 80/6527, which contains previous related correspondence, documents the recall and disposal of Convict records between 1869 and 1880, in particular the very significant destruction of Convict records (by pulping) which took place in late 1870.

The most interesting papers are those from mid to late 1870 which document the destruction. An August 1870 letter from the Inspector General of Police, John McLerie, about Convict records for disposal and preservation, includes two lists, one of those books and documents which he recommended be retained, the other of those he considered should be immediately destroyed. He noted that he did not suppose that the two lists were perfect as the records were ‘in such a complete state of confusion’ but that he would take ‘every precaution practicable to prevent the destruction of documents likely to be of any value’.

The destruction list

(This and the other list can be found as enclosures to a letter dated 11 August 1870 from the Inspector General of Police, John McLerie, to the Principal Under Secretary of the Colonial Secretary’s Office, Henry Halloran, CSIL 70/6822 with CSIL 80/6527).

This List includes a number of records which obviously would be of immense value to current day genealogists and researchers of 19th century Australia. The loss of the General Convict Muster Books, the Court Books, the Black Books, the White Book and the Assignment Registers cannot be overestimated. Nonetheless perhaps the most regrettable loss relates to the last two items on this List – the books and papers from the Country Benches of Magistrates and the various papers (‘A large Number …’) which one can surmise are the Principal Superintendent of Convicts on-going records of the day to day management of the Convicts.

The only ray of sunshine relates to the Ticket of Leave Passports. We believe that these have survived and that they are the extant Butts of ticket of leave passports, 1835–69, NRS 12204 (SRNSW: [4/4235-80]; Reels 966-981). (An index is available on State Records’ website.)

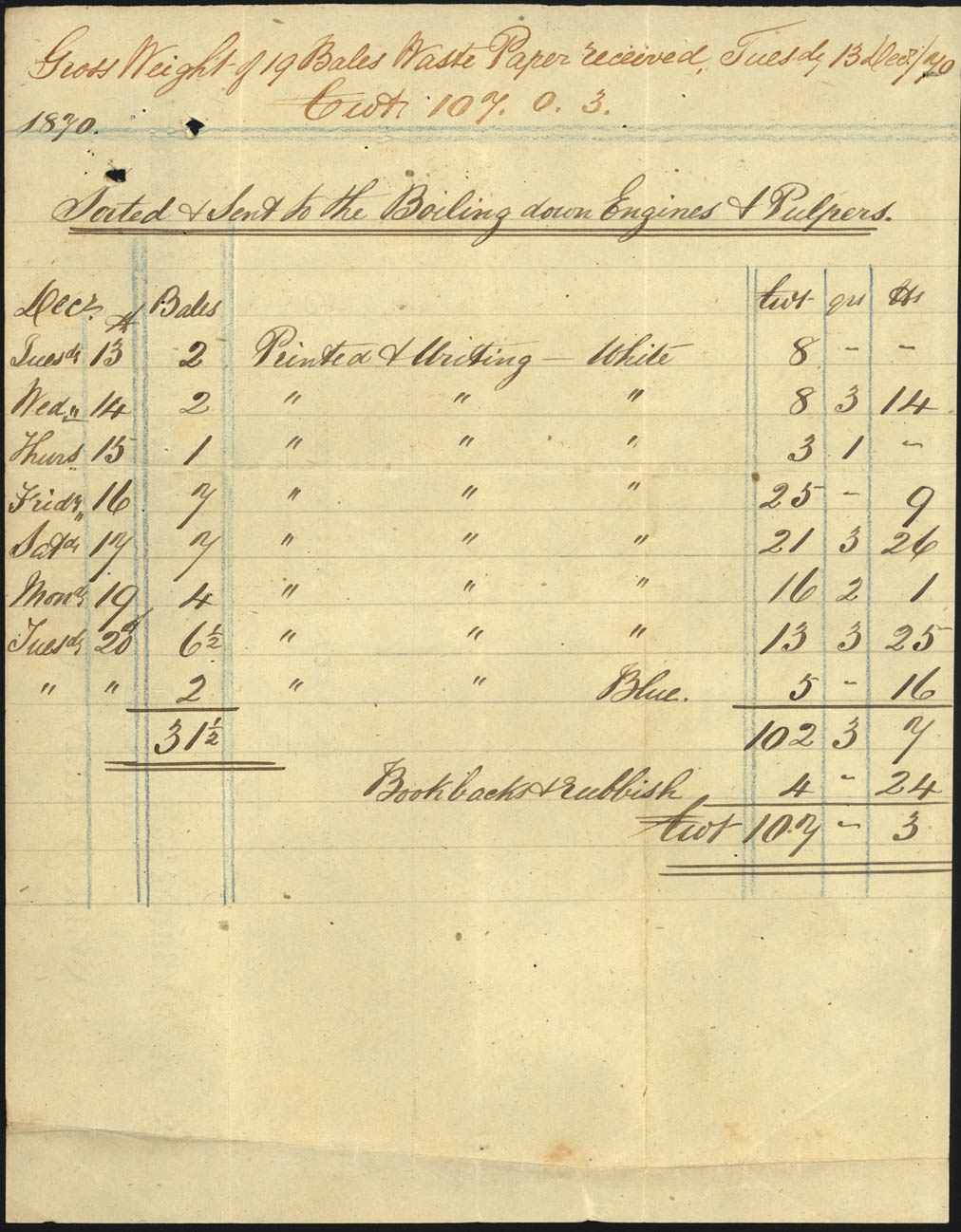

Unfortunately there was no last minute reprieve and destruction did go ahead. Oversighted by a Police Detective, the Imperial Convict records were destroyed by pulping between 13 and 20 December 1870. Excluding book backs and rubbish, the quantity pulped totalled just over 102 hundredweight or around 5.1 tons.

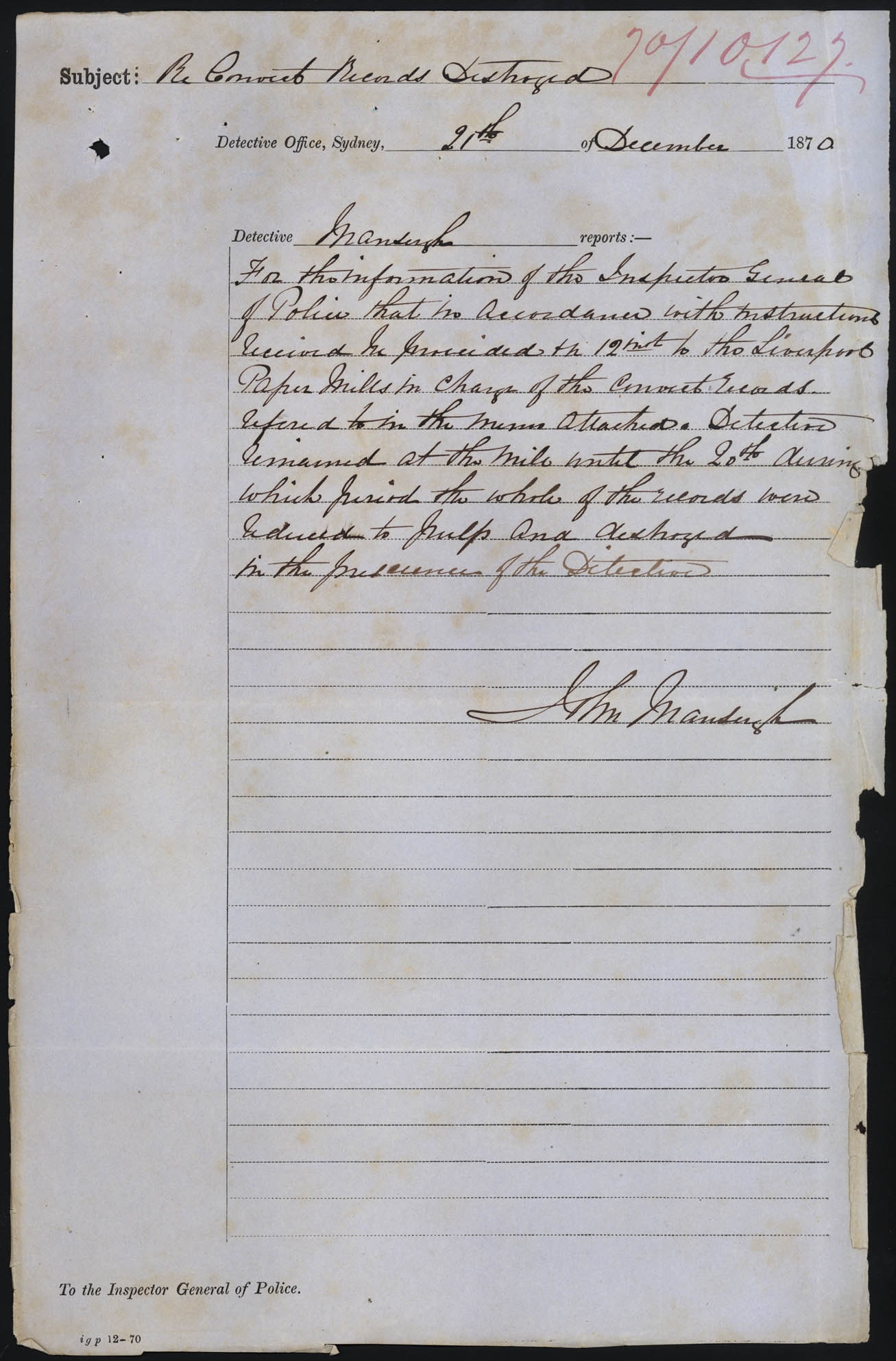

Report of Detective John Mansergh who supervised the pulping

(This report was sent by the Inspector General of Police in a letter to the Colonial Secretary dated 21 December 1970, CSIL 70/10127 in CSIL 80/6527)

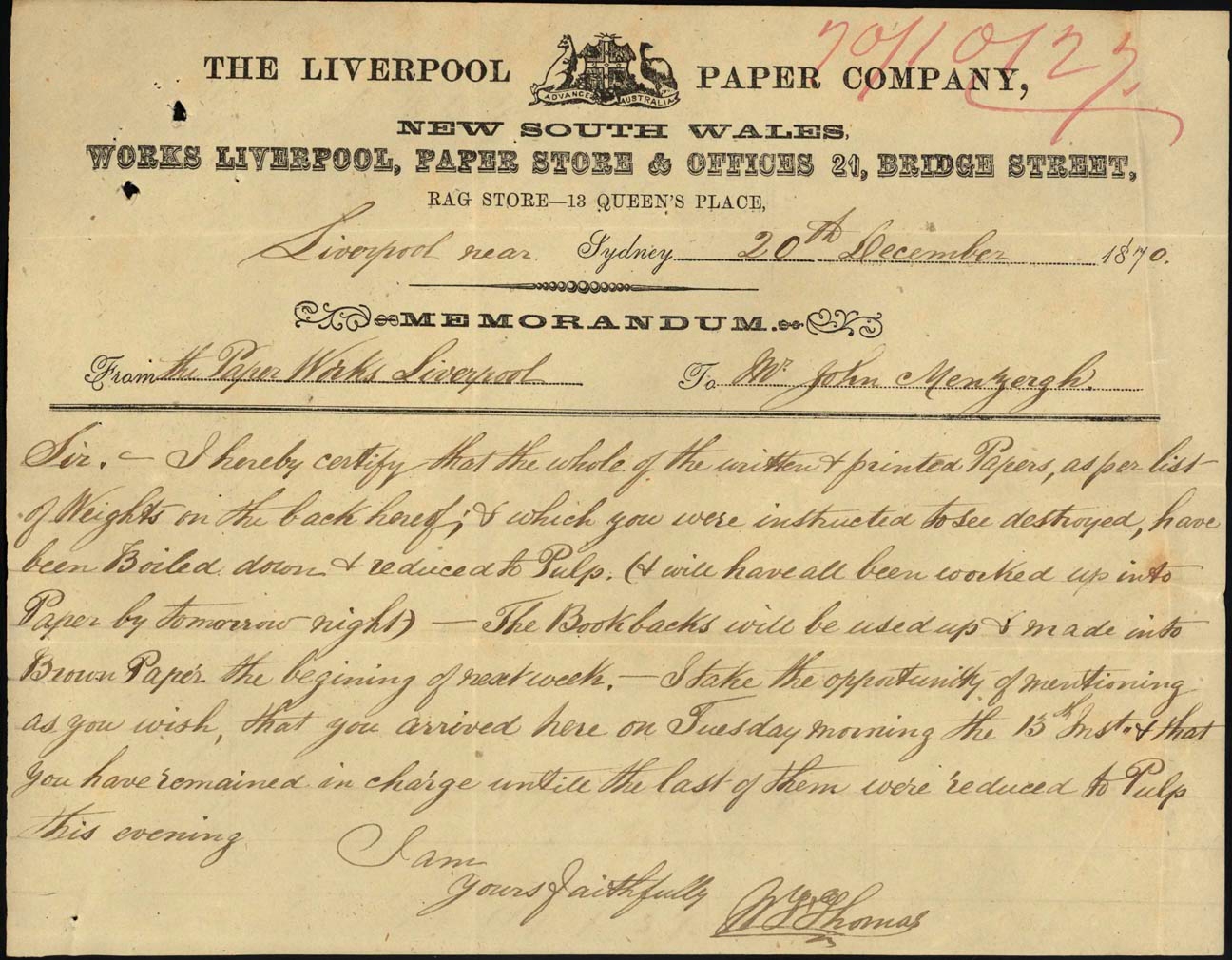

The Paper Mill’s official certification to the destruction of the records

(The certification by a Mr Thomas of the Paper Works Liverpool that the records were destroyed, also with CSIL 70/10127 in CSIL 80/6527)

(The other side of the certification giving details of the dates and quantities of papers destroyed at the Mill)

It is a sobering thought to contemplate the destruction of so many records now seen as significant; nevertheless, as an archivist, it is also gratifying to see that the destruction was not a haphazard affair but planned, duly authorised, well documented, and in accordance with Government policy of the day.

Christine Shergold

For more information about the systematic destruction of convict records in NSW please read “NSW Convict Records -“Lost and Saved” by Christine Shergold.

Jeannette says:

I’m not sure I can agree with Christine that it is gratifying that the destruction was ‘not a haphazard affair but planned, duly authorised, well documented, and in accordance with Government policy’. Give me haphazard any day. Then there’s a chance that something will still turn up. I’ve been working with a journal of a WNSW pastoral station manager – a daily entry for 5 years, 1862-67. The current owners believed that no records had survived, then this was found in 2003 by the family who owned the place in the 1860s. Since the manager was there for 25 years, I live in hope that the rest of his diaries could still be found. The clinical Government organised destruction makes my heart sink.

Jenny says:

It is interesting how the perceptions of what is a useful or valuable record/archive changes over time. When a practising archivist and records manager in a sector that lacks disposal schedules I probably veered moreto retention over destruction in devising schedules.

What someone sees as having no apparent value today may be a vastly different in years to come – for instance the official records for military vehicles in WW2 service were comprehensive but in the post war clean-up were perceived as having no informational value and were largely destroyed. To vehicle restorers and military researchers today those records would be precious. As indeed would the ‘old’ motor vehicle registration records for NSW that were destroyed by the Dept. of Motor Transport some years ago.

Determing what to keep and what to let go, apart from legal requirements, is never an easy task, as you are predicting what information people will want in years to come.