Category Archives: Preservation

Valuable for other reasons: the survival (or not) of glass negatives

Glass is generally more stable from a conservation viewpoint than film when used as the support or medium for a negative (despite the brittleness of glass). So I was interested to read Sandy Barrie’s essay ‘Why no Negs or records survive?’ in his book Australians Behind the Camera: directory of early Australian photographers 1841 to 1945 (The author, 2002).

Barrie’s work continues the listing of Australian photographers begun by Allan Davies, Peter Stanbury and Con Tanre in The Mechanical Eye in Australia : photography 1841-1900 (Oxford Uni Press, 1985).

This image was scanned from the original glass negative taken by Ralph Snowball. It is part of the Norm Barney Photographic Collection, held by Cultural Collections at the University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia.(Note the silvering around the edges of the negative as the emulsion deteriorates.)

Survival of the fittest?

As a practising photographer who worked in major studios, Barrie offers some insights into why negatives did not always survive.

- Commercial photographers were a business. Anything that would not generate continuing profit over time was a liability. Images that had long term commercial value were portraits of prominent people, landscapes and in Barrie’s words ‘newsworthy shots’. As historians the images that we search for may either have not been taken in the first place or if they were taken, were not judged as valuable enough to retain for the long term.

- There is the volume of negatives produced by studios. Barrie notes that the Tuttle Studios of Sydney took 30,000 portraits in 1897 alone. To add perspective to this statistic there were 57 photographers operating in the Sydney area in 1897 according to the Trade section of the Sands Directory.

- There is the large amount of space needed to store negatives, particularly if you were renting prime city real estate.

- Glass is heavy. As Barrie states ‘when you shoot several thousand negs a year, that adds up to a large Tonnage. There were even some notes in the early RPS journal of studio buildings collapsing under the weight, when photographers stored negs in their attics.'(p234) This led some photographers to store their negatives under their premises. For example if it is estimated that each 8″x10″ glass negative weighed 0.3kg, the output of Tuttle Studios for 1897 (see above) would weigh approximately 9,000 kg.

- Negatives could be cleaned of their image and recycled into two products that had value – the glass itself and the silver emulsion used to create the image. Companies would buy back negatives from commercial photographers to recover the silver. Photographic silver was rare during World Wars I and II and almost all silver was reserved for defence purposes in the latter. The Great Depression also saw large scale cleansing of glass negatives as commercial photographic sales fell and photographers needed income. Mr Barrie has told us that towards the end of World War II, Kodak had no means of making film base for cellulose negatives in Australia and many commercial photographers actually went back to using glass negatives.

Despite the breakage it has suffered this 1885 Bischoff image still retains its informational value.

I have always valued the images that survived. Now I will also value the glass negatives’ bulk and weight as a testament to that survival.

Help Sandy Barrie with his Research

Sandy Barrie can be contacted on apbarrie@dodo.com.au and is keen to hear from the relatives of Australian photographers. He is preparing a new edition of his book, which thanks to the National Library of Australia’s Trove will contain almost three times the data despite the impact on his research of the January 2011 Queensland floods.

Jenny Sloggett is an Archivist working in the Archives Control and Management section of State Records NSW.

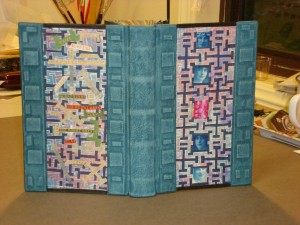

Listeners in the Mist – Episode 16: Book Conservation with Jill Gurney

Listeners in the Mist is a series of podcasts produced by Blue Mountains City Library. It is book lover heaven. I can definitely recommend having a trawl through their interviews.

In this instalment Book Conservator Jill Gurney is interviewed by Naomi and discusses her career and the intricacies involved in her work.

N.B. If the embedded player doesn’t work for you check it out at the source

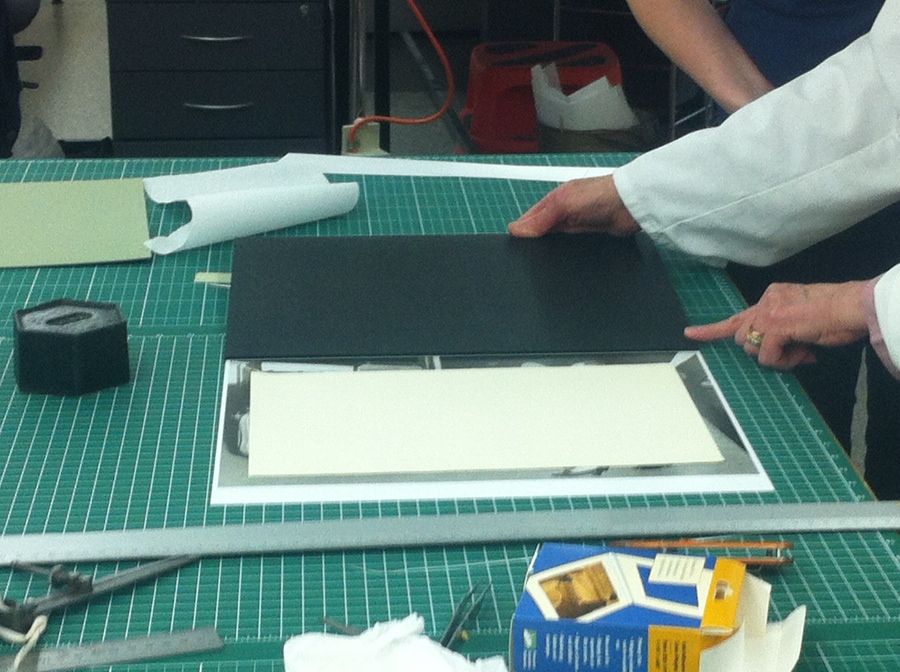

Box making – high-tech style

Visit the preservation lab at the US National Archives in this YouTube video (2:56mins) and see how boxes are made. Not by hand or with a measuring tape but by machine.

A loft conversion with a difference

As many of you would know using a roof space for archival storage presents a lot of challenges, however, the Justice and Police Museum have embraced the challenge and effected a stunning transformation.

Conservation Tip No 8: Removing chewing gum from paper documents

Can you give info on removing chewing gum on reverse side of an important document? There is a small quantity of gum still in place – fairly fresh, a circle of about 1/2 inch. Some stain has bled thru to front.

Cool Tools – Calculators for Environmental Conditions

I found the environmental calculators made available by the Image Permanence Institute to be tremendously helpful so I thought I would share.

Rolling back into history [Conserving a 13 metre petition from 1862]

The problem for anyone who wanted to read the document was that in order to open up the petition, the entire length needed to be unrolled first. Once unrolled, there was the issue of trying to safely open a 13 metre fold!

Celebrating our Audiovisual Heritage

Thursday 27 October is a special day for many archivists, it’s UNESCO World Day for Audiovisual Heritage. This year’s theme, ‘Save and savour your Audiovisual Hertiage – Now!’ will be celebrated by many audiovisual archives around the world…..